Grace Clover and Lena Winzer, FRFG project managers, reflect on their visit to the Longplayer in London last week.

As the FRFG wrote in 2023, protests, demonstrations, and new studies can be critical in drawing attention to intergenerational justice. But these are not the only ways. Art too can play a central role in thematising intergenerational issues and long-term thinking.

‘Long Term Art Projects’ is an informal association of long-term art projects founded in late 2022, including Future Library in Oslo, the Letters of Utrecht, the Long Now Foundation’s Clock, and the Zeitpyramide in Wemdinger, Germany. These projects seek to make ‘deep time’ tangible, extending our perspectives long beyond the span of a single human lifetime. In highlighting how short a single human life is in comparison to the geological age of the natural world, these artworks seek to draw us out of short-term cycles of economic gain, sensationalist media preoccupations, and brief electoral periods. They instead promote a ‘long view’. This kind of art might be seen as an antidote to what is called ‘presentism’, understood as a bias in our laws, political systems, economies and thought processes towards the present, neglecting the needs of the future and future generations. ‘Presentism’ is distinct from necessary responses to short-term emergencies and very real problems in the present, but rather refers to the blinded ignorance of slow-burning and cascading risks such as climate change and over-burdened welfare systems. As a term, it draws attention to the fact that we mistakenly assume that the future will be less real and somehow less painful than the present.

On Saturday 5 April 2025, we had the fantastic opportunity to attend the 25th anniversary of the Longplayer (pictured above), one such long-term art project. The Longplayer is a one thousand year long musical composition, which began playing at midnight on the 31st of December 1999, and will continue to play without repetition until the last moment of 2999. At this point, it will complete its cycle and begin again. Conceived and composed by Jem Finer, the Tibetan bowls have been played consistently since the last millennium. Normally, Longplayer plays in the lighthouse at Trinity Buoy Wharf in East London, its original and enduring home since its conception. In honour of this anniversary, however, the Longplayer was moved to the Roundhouse in Camden, London, for a weekend of celebration, reflection, and discussion. It can also be accessed via live stream online, or at several listening posts around the world. Its continuity is ensured by the Longplayer Trust, a small group of custodians responsible for maintaining its sound and survival.

From its initial conception, a central part of the Longplayer project has been about considering strategies for the future. How does one keep a piece of music playing across generations even after its original custodians are no longer around? The idea of the Longplayer is to make time tangible and to encourage long-term survival strategies, in a time where short-term decision-making is still the predominant status quo. What makes the Longplayer so remarkable is not only the sheer duration of its composition, but the philosophical questions it quietly asks of its listeners: what does it mean to sustain something for a millennium? What infrastructures must be imagined, technically, socially, politically and intergenerationally, for a piece of music to endure? Composed for Tibetan singing bowls, Longplayer’s sounds are both meditative and mechanical, physical and ethereal. The composition is algorithmic, unfolding based on a simple but elegant set of rules, producing harmonies that shift slowly across days, years, and centuries. Though its structure is predetermined, no single listener will ever hear it in its entirety. It exists beyond human scale, yet it depends entirely on human care.

This anniversary weekend at the Roundhouse was a rare moment in Longplayer’s quiet continuum, creating a space where listeners, composers, artists, and future-thinkers could come together in reflection. Surrounded by the resonant tones of the bowls and a community of fellow listeners, we were reminded that Longplayer is more than music: it is an ongoing conversation between generations. As we sat within the circular embrace of the Roundhouse, itself a repurposed Victorian railway building, the symbolism was hard to miss: an old space holding a vision for the far future. Panels, live performances, and installations over the weekend highlighted Longplayer’s ethos of long-term thinking and stewardship. From discussions on post-digital preservation to human-powered versions of the composition, the weekend invited participants to consider the continuity of human community and the natural world not as a passive occurrence, but as a collaborative act.

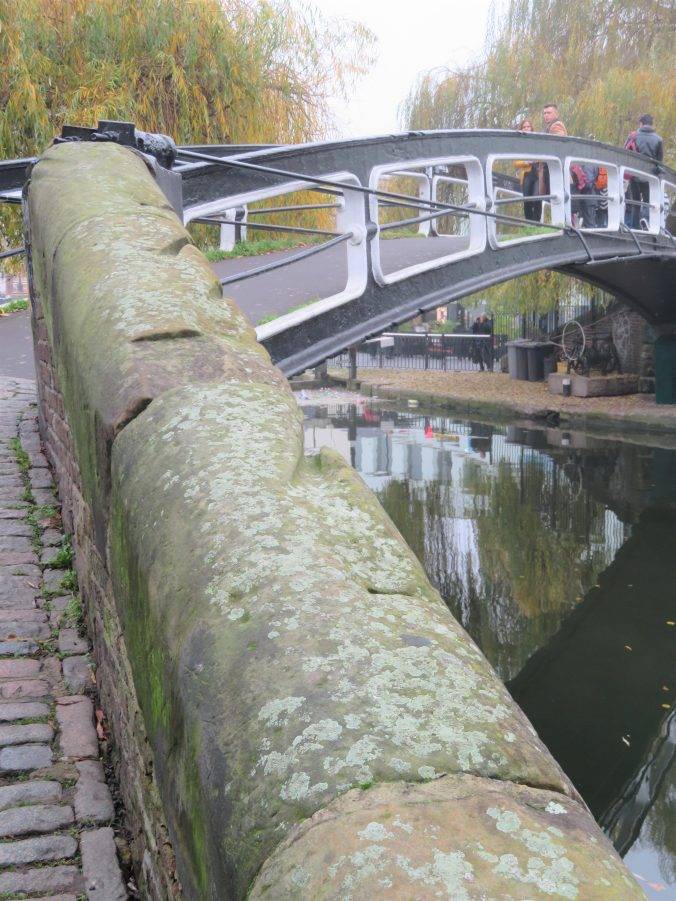

As part of this weekend-long symposium focusing on long-term thinking, we met many inspiring people working in the field of long-term thought, sustainable policy, and intergenerational justice. We participated in a circular walk (reflecting the circularity of the Longplayer and our need to remove ourselves from linear narratives of ‘progress’) around Primrose Hill led by Robert Kingham, where we learnt about the local history of the area. In walking through this historic neighbourhood, we were encouraged to open our eyes to the tangible evidence of the past all around us. For example, the grooves in the iron and stone tow bridge across Camden Lock (pictured here) made by hundreds of horse-pulled tow rope which dragged barges upstream from the 1740s to the early 20th century. This was a key example of how repeated historical practices have left visible marks on the world around us. Looking back much further, we learnt about the history of the 50 million-year-old Eocene London Clay and chalk that formed the Primrose Hill.

But what is the value of opening up our eyes to history and geology? And how does this relate to long-term art? In fact, looking forwards and looking backwards are two sides of the same coin. In turning our attention to the deep geological and anthropological time around us, it becomes clear that we are only custodians of the world for people in the future, be that in 5, 50, or 5000 years. As the Seventh Generation Principle teaches us, it is valuable to look at how our ancestors have influenced us and our world, so as to see how our actions will impact the future generations. Reconnecting with the natural world and reframing our attitude towards time can act as an antidote to the rampant short-termism and overconsumption of the present.

Of course, this kind of perspective shift must facilitate changes in our behaviours, and also changes in policy. On a personal level, for example, we must begin to consider our individual obligations towards the environment, and choose to limit our output of carbon dioxide. On a societal level, we must urgently respond to issues such as demographic change, global warming, and public debt to avoid dramatic implications for future generations.

As Richard Fisher, author of The Long View told us in a testimony about the value of long-term thinking: “It’s easy to assume future generations exist in a far-away place, distant from our lives in the present. That’s not true – in fact, many citizens of the 22nd Century already live among us, as children. To gift them a better world, we must take the long view.”